- This event has passed.

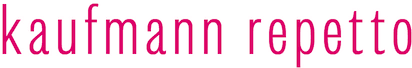

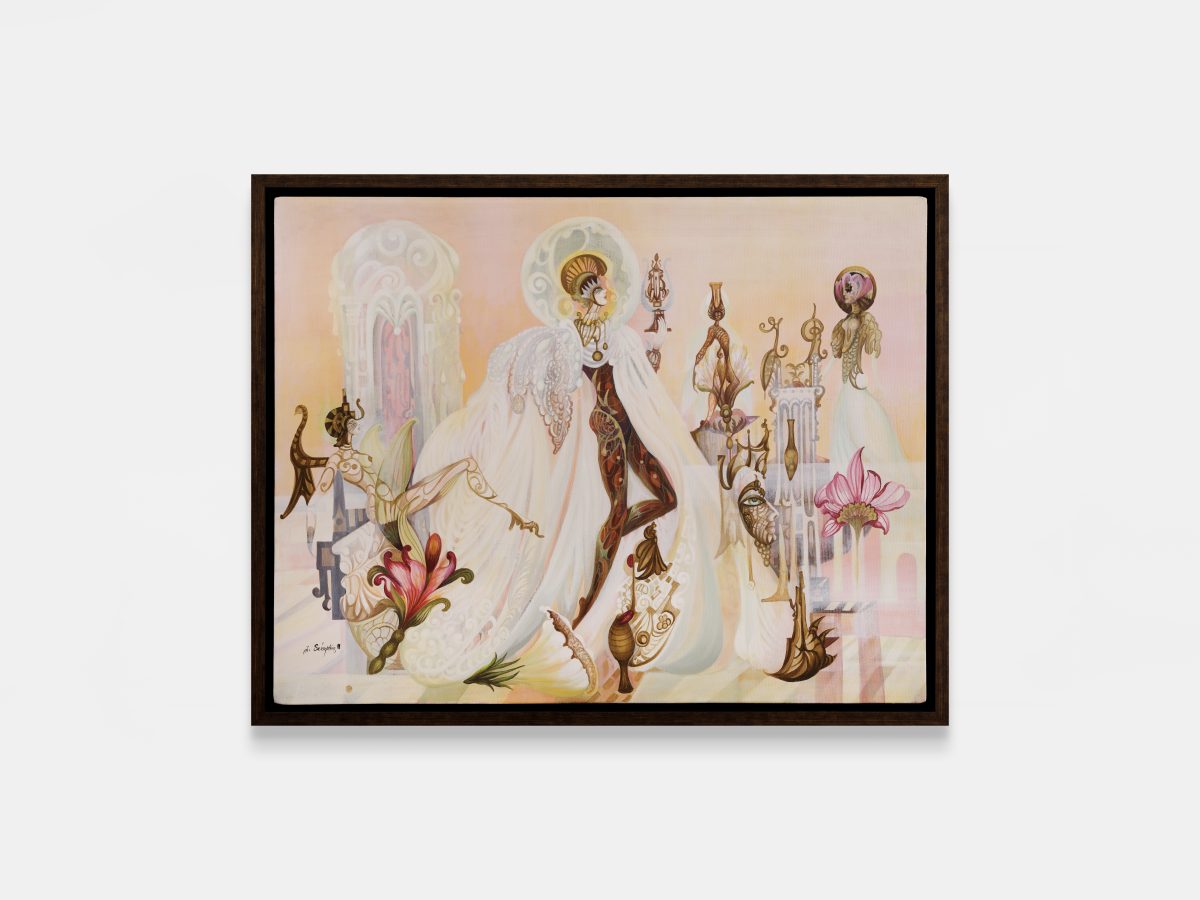

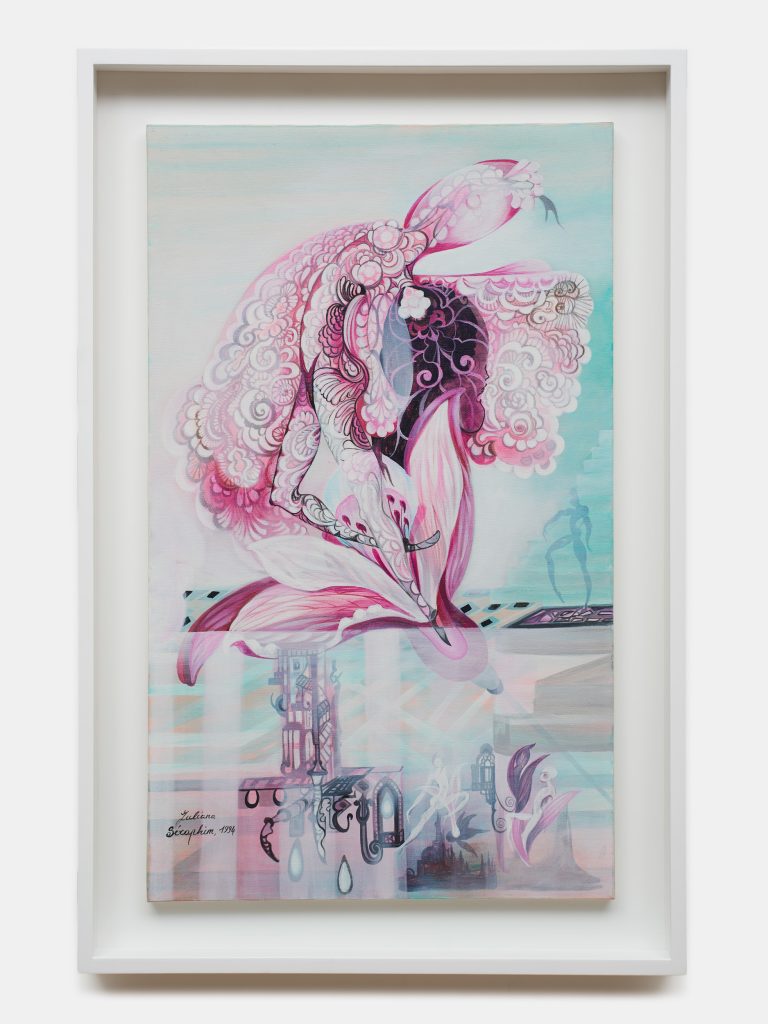

(55 Walker) is pleased to present Juliana Seraphim: The Flower Woman, opening Thursday, June 26.

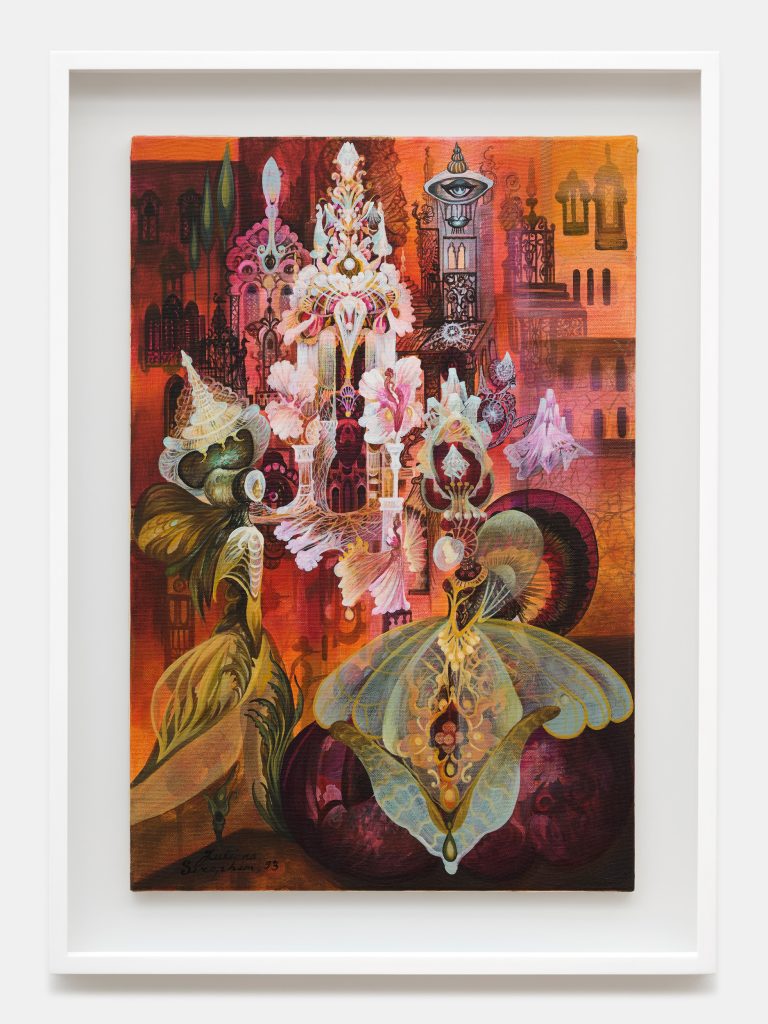

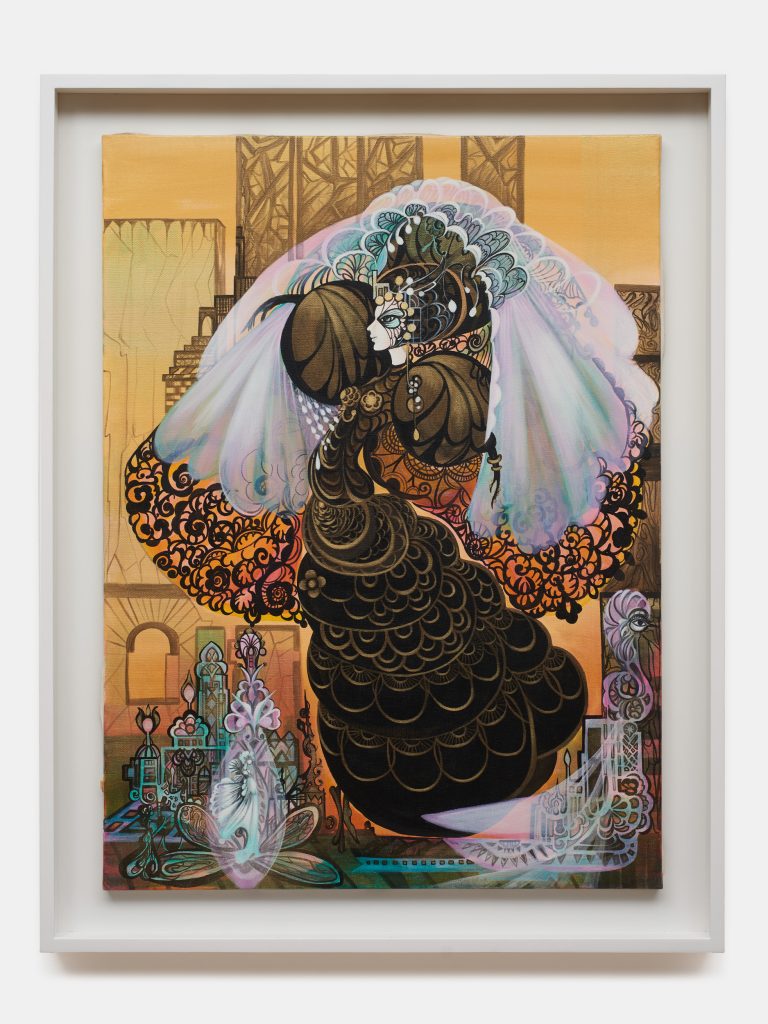

Juliana Seraphim’s singular surrealist style and embrace of desire and female subjectivity redefined the modern art landscape of the Middle East. Born in Jaffa, Palestine, Seraphim’s early years were profoundly shaped by her family’s arrival in Lebanon following the start of the Nakba in 1948. This early experience of displacement and exposure to a marred and discriminatory world indelibly informed her work. Through sensuous detail and phantasmatic figures, Seraphim built an iconog-raphy rooted in the perception of a “woman’s world,” exploring sensuality, selfhood, and spiritual longing. Spanning four decades, the exhibition traces the evolution of Seraphim’s oeuvre, beginning with her abstract cityscape paintings from the early 1960s. Works such as Clear Winter Night under the Snow in Baalbek (c. 1960s) exemplify her early engagement with architectural motifs. By the 1970s, Seraphim’s surrealist style had fully emerged in works like Untitled (1978), where eyes, sea life, and ethereal female forms coalesce in scenes lush with myths and subconscious memory. These works reveal her inspiration from the Italian frescoes that adorned the ceilings of her grandfather’s home in Jerusalem, as well as the seashore near Jaffa, where she often played as a child. Changes in Lebanon’s political situation—particularly the status of Lebanese women—are echoed in Seraphim’s shift from impressionistic abstractions to intricate figurative works: “Lebanon today is not the same as Lebanon yesterday. Transformation was inevitable,” the artist lamented in a 1992 interview in Al Ousbouaa Al Aazi. Despite tragedy, she looked to the steadfastness of Lebanese women, who “arm themselves with hope and faith—one of the secrets to Lebanon’s survival.” The 1990s demonstrated a period marked by increasingly detailed and dream-like compositions. In these works, branching black and metallic gold lines adorn forms at once figurative and botanical. Dream of Samarkand (1994) and Orphée (1998) burst with flowers, masks, and female figures ren-dered in sumptuous detail, merging erotic energy and mythic overtones with ghostly architectural forms that echo her earlier influences. Here, Seraphim’s women are depicted winged and diaphanous, floating over cities in triumph and liberation. Seraphim’s candid articulation of female sexuality and agency positioned her as a true visionary, a worldbuilder in life and in art. Her work challenged the patriarchal norms of her time, presenting femininity as multifaceted, sensual, and emotionally complex.