- This event has passed.

In the summer of 1968, Sister Mary Corita took leave of upheaval, turmoil, and controversy. While on sabbatical as a teacher with the order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles, she headed to her friend and gallerist Celia Hubbard’s house on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. She was free to think about her artwork, have picnics on the beach, shed a skin of duty, and live simply as herself — or to find out who that could be. She was fifty years old; she was becoming Corita Kent.

The decision to dispense with her religious vows was her own, but she couldn’t have managed it by herself. Having never rented an apartment — or even, despite having grown up in Los Angeles, learned to drive — she moved into Hubbard’s living room in the Back Bay of Boston, and after two years, another brownstone near Copley Square with a bay window overlooking a maple tree. She hadn’t abandoned her past though; far from it — she made regular trips back to Los Angeles to see former colleagues and friends, or to work with her North Hollywood gallery, and they visited her back East as well. Corita’s former student from Immaculate Heart College, Mickey Myers, reunited with her after moving to Boston. By 1971, Kent’s artistic practice had shifted, and she had her first show of watercolors in Los Angeles, the same year as her most high-profile commission: covering a 150-square-foot storage tank with a rainbow swash for Boston Gas. But concurrent with her heightened public presence and graphic work benefiting organizations and causes she believed in, it was watercolor painting — direct, intimate, and exploratory — that became the primary medium she would use for the rest of her life.

It was in England during the Romantic period when watercolor painting en plein air became more widespread, popular, even common. The freer brushwork more readily captured fleeting atmospheric effects, and it attracted both professionals and amateur artists. Notably the medium influenced the rise of Modernism, catching the attention of the early Impressionists, as well as of the 20th century Avantgardists Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. For a short article published in early 1925, titled “Watercolors,” the Swiss writer Robert Walser penned a suitably light and direct impression of the medium’s practitioners: “[the watercolorist] documents his own good judgment, his feeling for what is.” He identified their work as an appeal to “common sense.” Kent advocated for something similar in her work, to see things “as simple as they really are,” which “means that we see the relationships between everything and know that it’s all just part of us and friendly and flowing in an unknown but a rhythmic pattern.” She didn‘t underestimate a larger context in the struggle to maintain an artistic process amongst the reality of what “is.” A brilliant writer herself, she considered art “whatever you may do amid adversity for the common good.” This is excerpted from a posthumously published article titled “The Artist as Social Activist amid Adversity: How the Job Is Done,” composed in 1984, wherein she also asserted: “I think we have to have the awareness that everything is sacred, and when we lose that awareness we lose connection with the whole, with the cosmos. . . . A picture may be a symbol for the whole if we look at it as a small cosmos.” While many of Kent’s watercolors were translated into prints, it is the paintings’ unmediated qualities which best speak to the tone of her maturing practice, and life, as an observer of details that could serve as symbols for a common, even sacred, whole.

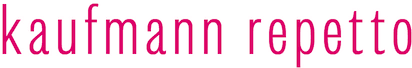

The watercolors in this show span the years 1980–86. Her Bay Area print dealer, Marlene Teel-Heim, thought that the medium had particular significance for the artist, given that “watercolors were so much more spontaneous because you had the result right in front of you, right then and there.” Kent would often manage to make it home with a handful of paintings, made en plein air, after expeditions around New England with her longtime friend, Elinor Mikulka. In one of these paintings, dated 1982, there’s a suggestion of a road winding between two hillsides and disappearing into a thicket of burgundy. Mikulka did the driving — perhaps this is an implicit acknowledgment of her, or a symbolic rendering of one ordinary road that stands in for all the others they went down together.

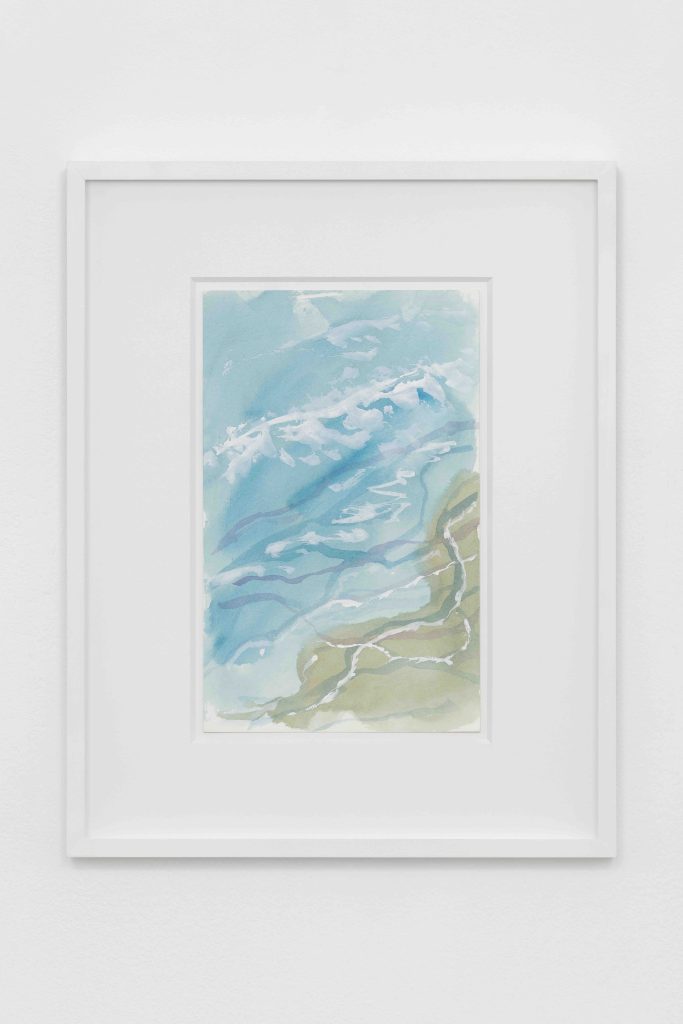

Another of the paintings poetically holds a similar tension between absence and presence. A pale, walnut-colored wash surrounds a white flower and embellishes its stem with a few flicks of the brush. The floral contours are articulated by the negative space of paper, unpainted. Flowers were a favored subject for Kent, and not as some decorous motif but rather as evidence of her equanimity and philosophical approach to art and life. On her creative process later in life, she observed that a flower “has its own language, but it’s not beneath our language; it’s not different in kind; it’s only different in quality.” Another watercolor from 1984 shows a pencil drawing of a rose with its fuchsia petals painted wet-on-wet, as if whispering to — rather than shouting about — the nature of life, as a composition of layers that hold together before giving way to its absolute promise to fall apart, or dissolve together. A watercolor is a painting, but it is often also, as Walser might say, a documentation: Of where one goes, has been, or is. The paint settles as a memory might — lightly, with a chance of fade.

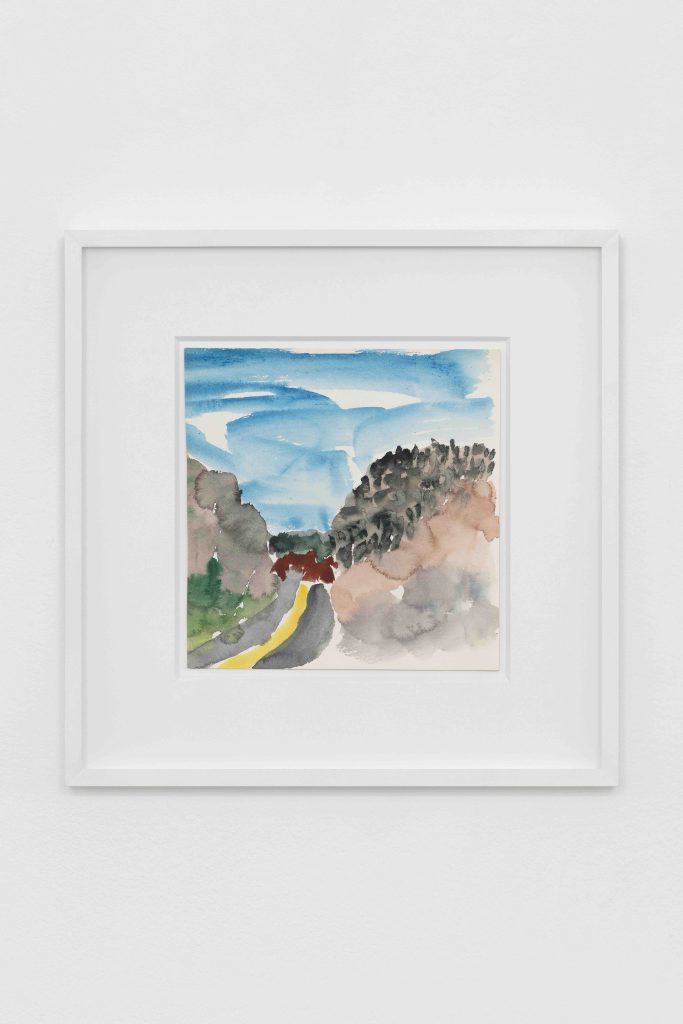

Two paintings each from the last two years of her life render the waves of the ocean as fluid lines and daubs, coursing as they might, and will. She was seeing the world around her and taking it by the brush in her hand — greeting it, and holding it, in relation and conversation. By 1986, Kent had decided to fight the return of her cancer, as she told Myers, with an open hand, not a fist. The free, flowing brushstrokes of these paintings, made in her final years, tell a similar story.

– Paige K. Bradley

Nell’estate del 1968, Sister Mary Corita si prese una pausa dal trambusto, dal fermento e dalle polemiche. Lasciò l’insegnamento presso l’ordine del Cuore Immacolato di Maria di Los Angeles per prendere un anno sabbatico, e si recò a casa dell’amica e gallerista Celia Hubbard a Cape Cod in Massachusetts. Era libera di pensare al proprio lavoro artistico, fare picnic sulla spiaggia, spogliarsi dell’abito talare e vivere semplicemente come se stessa — o scoprire chi questa se stessa avrebbe potuto essere. Aveva cinquant’anni; stava diventando Corita Kent.

La dispensa dai voti religiosi fu una sua decisione, ma non avrebbe potuto farcela da sola. Non avendo mai affittato un appartamento — o addirittura, pur essendo cresciuta a Los Angeles, imparato a guidare — si trasferì nel salotto di Hubbard nel quartiere Back Bay di Boston e, dopo due anni, in un’altra abitazione vicino a Copley Square con un bovindo affacciato su un acero. Ma non aveva dimenticato il proprio passato; anzi — faceva regolarmente avanti indietro con Los Angeles per andare a trovare ex colleghe e amici, o lavorare con la propria galleria di North Hollywood, visite che venivano ricambiate. La sua ex studentessa dell’Immaculate Heart College, Mickey Myers, la raggiunse dopo essersi trasferita a Boston. A partire dal 1971, la pratica artistica di Kent era cambiata e lei tenne la sua prima mostra di acquarelli a Los Angeles nello stesso anno in cui ottenne la sua commissione di più alto profilo: coprire con strisce arcobaleno un serbatoio di stoccaggio della Boston Gas alto 46 metri. Ma in concomitanza con l’aumento della sua presenza pubblica e del suo lavoro grafico a favore delle organizzazioni e delle cause in cui credeva, la pittura ad acquarello— diretta, intima ed esplorativa —diventò la tecnica principale che avrebbe impiegato per il resto della sua vita.

Fu nell’Inghilterra del Romanticismo che la pittura ad acquarello en plein air si diffuse maggiormente e divenne una pratica comune e molto apprezzata. La pennellata più libera catturava prontamente fugaci effetti atmosferici e attraeva artisti tanto professionisti quanto amatoriali. Il medium influenzò in particolare la nascita del Modernismo, attirando l’attenzione dei primi impressionisti, come anche degli avanguardisti del ventesimo secolo come Wassily Kandinsky e Paul Klee. In un breve articolo dal titolo “Watercolors” pubblicato agli inizi del 1925, lo scrittore svizzero Robert Walser tracciò un’immagine delicata e diretta di chi si dedicava a questa tecnica: “[l’acquarellista] documenta la propria buona capacità di giudizio, il proprio sentimento per ciò che è”. Ne definiva l’opera come un appello al “buon senso”. Kent sosteneva qualcosa di simile nel proprio lavoro, il vedere le cose “semplici quanto lo sono in realtà”, che “significa che noi osserviamo i rapporti tra ogni cosa e sappiamo che tutto fa parte di noi ed è in equilibrio e scorre secondo uno schema sconosciuto ma ritmico”. Nello sforzo per mantenere un processo artistico nella realtà di ciò che “è” non sottovalutava un contesto più ampio. Lei stessa una brillante scrittrice, considerava arte “qualsiasi cosa fosse fattibile per il bene comune tra le avversità”. La frase proviene da un articolo pubblicato postumo dal titolo “The Artist as Social Activist amid Adversity: How the Job Is Done”, scritto nel 1984, nel quale affermava inoltre: “Penso che dovremmo avere la consapevolezza che ogni cosa è sacra, e che quando perdiamo questa consapevolezza perdiamo il nostro legame con il tutto, con il cosmo… Un quadro può essere un simbolo per il tutto se lo guardiamo come un piccolo cosmo”. Anche se molti acquarelli di Kent sono stati trasposti in stampe, sono le qualità immediate dei quadri che meglio esprimono la sfumatura della sua pratica, e vita, in maturazione come osservatrice di dettagli che potrebbero fungere da simboli per un insieme, comune ancorché sacro.

Gli acquarelli di questa mostra abbracciano gli anni tra il 1980 e il 1986. La sua gallerista per la Bay Area californiana, Marlene Teel-Heim, pensava che il medium avesse un significato particolare per l’artista, poiché gli “acquarelli erano molto più spontanei dato che avevi il risultato subito davanti ai tuoi occhi”. Dalle sue spedizioni in giro per il New England con la sua amica di lunga data Elinor Mikulka, Kent tornava spesso a casa con un po’ di quadri, realizzati en plein air. In uno di questi, datato 1982, è accennata una strada che curva tra due colline scomparendo in una boscaglia bordeaux. Mikulka guidava — forse rappresentava un implicito riconoscimento nei suoi confronti, o una rappresentazione simbolica di una strada comune che rappresenta tutte quelle percorse assieme. Un altro dipinto contiene una tensione simile tra assenza e presenza. Un lavaggio beige attorno a un fiore ne abbellisce lo stelo con qualche colpo di pennello. I contorni floreali sono resi dallo spazio negativo della carta, non dipinto. I fiori erano un soggetto prediletto da Kent, non come un qualche motivo decorativo ma piuttosto come testimonianza della sua equanimità e del suo approccio filosofico all’arte e alla vita. A proposito del suo processo creativo in età avanzata, osservò che un fiore “ha il suo proprio linguaggio, che non è un linguaggio inferiore al nostro, ma solo diverso in qualità”.

Un altro acquarello del 1984 mostra una rosa con i suoi petali fucsia dipinti alla prima, come in un sussurro alla — piuttosto che un grido sulla — natura della vita, come una composizione di strati che resta unita prima di cedere il passo alla sua promessa assoluta di sfaldarsi, o dissolversi. Un acquarello è un dipinto, ma spesso è anche, come direbbe Walser, una documentazione: di dove si è diretti, si è stati o si è. Il colore si deposita come potrebbe farlo una memoria — delicatamente, con una possibilità di svanire.

Due dipinti, uno per ognuno degli ultimi due anni della sua vita, rappresentano le onde dell’oceano come linee fluide e pennellate che scorrono come potrebbero e faranno. Stava osservando il mondo attorno a sé e cogliendolo tramite il pennello nella sua mano — accogliendolo e trattenendolo, in relazione e conversazione. Nel 1986, Kent aveva deciso di combattere il ripresentarsi del tumore, come disse a Myers, con la mano aperta, non con il pugno. Le pennellate libere e fluide di questi dipinti, realizzati nei suoi ultimi anni, raccontano una storia simile.

- – Paige K. Bradley