- This event has passed.

kaufmann repetto is glad to announce GROW, Judith Hopf’s fourth solo show with the gallery, where the artist presents new works (sculpture and silkscreen prints) that reflect critically on the privileged place of the human species in the hierarchical structures of being.

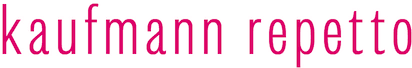

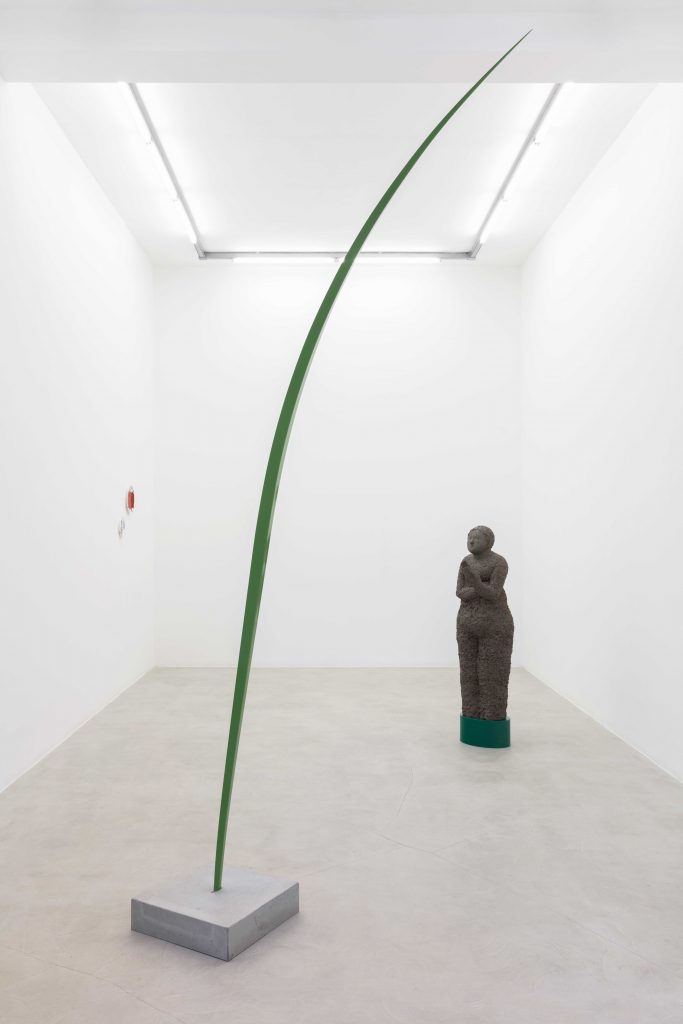

With Phone Users 1, 2, 3 humans appear on the scene under the form of life-sized sculptures made of clay, a figurative representation unparalleled in the artist’s practice. Shaped by hand-formed chunks, the crumbly outlines of their bodies and facial features are roughly sketched. Captured in the silent and motionless isolation of their raw and brittle materiality, each of the three figures represents a person who is grasping a phone. Their gestures evoke a familiar experience that we all know well from our everyday lives: they are portrayed in the attempt of receiving, recording or transmitting the signals of telecommunication. But whether holding up the phone in search of reception or clumsily bending over the screen while sending a message, these Phone Users seem to be struggling, as if it was not even clear to themselves what exactly they are supposed to receive. Their facial expressions convey a sense of bewilderment, incredulous that their connection to the world doesn’t work as they imagined.

The concern for the interrelation between humans and technology is a recurring theme in Hopf’s oeuvre, like for instance in Laptop Men, an earlier series consisting in abstract figures made of geometrically shaped metal sheets bearing cartoon-like faces. Also in Phone Users a total amalgamation between body and device has taken place, yet in this case a sense of resistance is conveyed through the rough materiality of clay, literally and symbolically close to earth. The plasticity and malleability of the raw material preserves the memory of the hand-shaped modelling, reproducing every handgrip and finger pressure with extreme precision – an ante litteram scanning process which acts as an antagonist to the contemporary digital dependance.

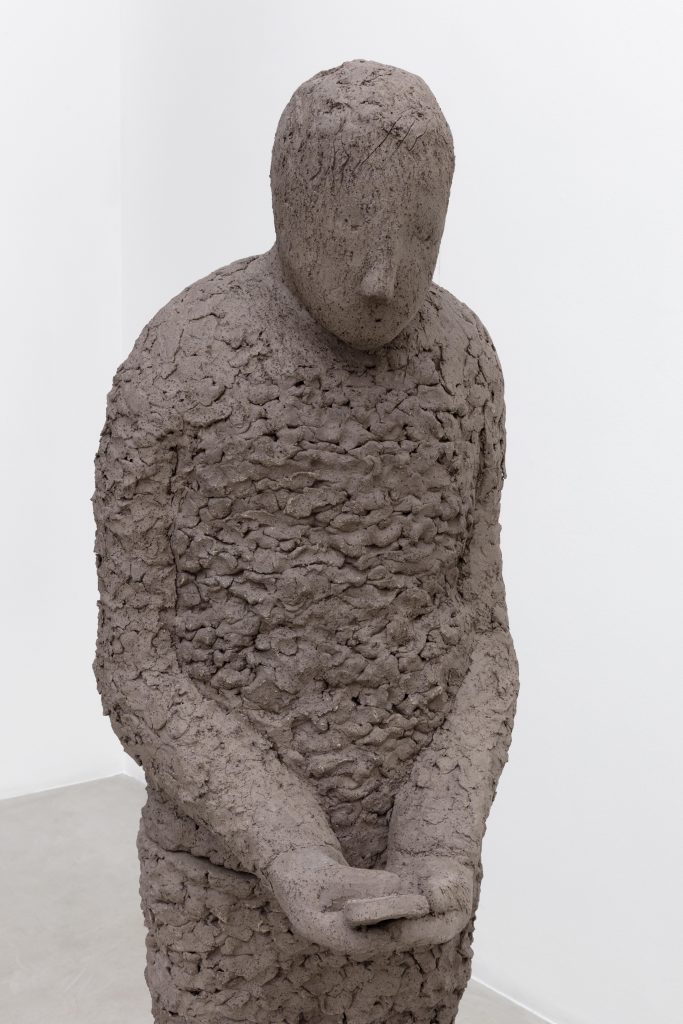

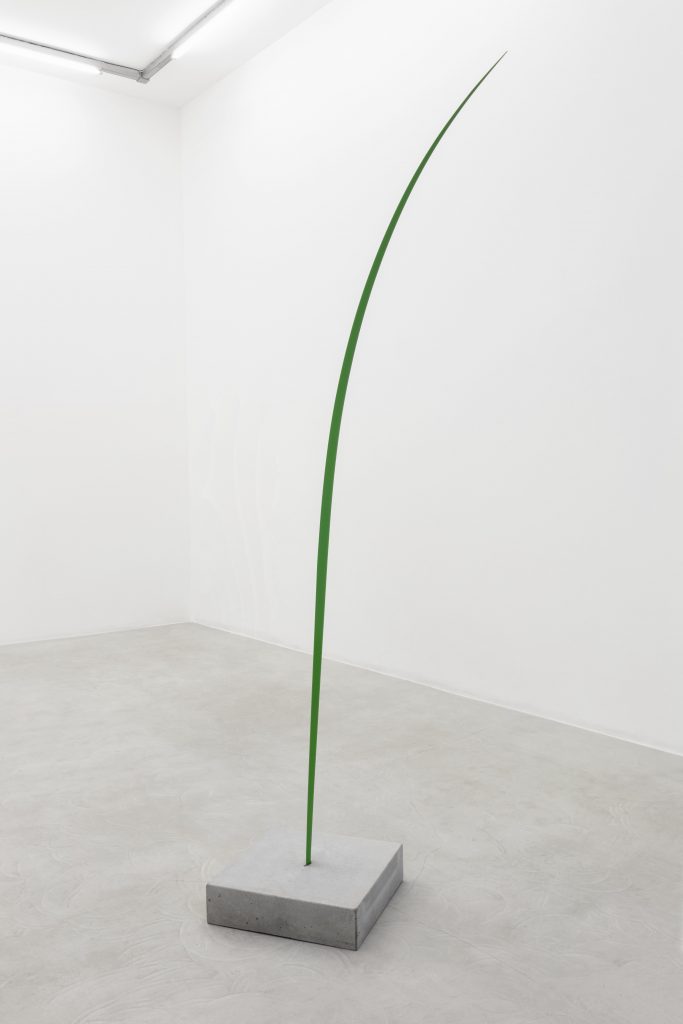

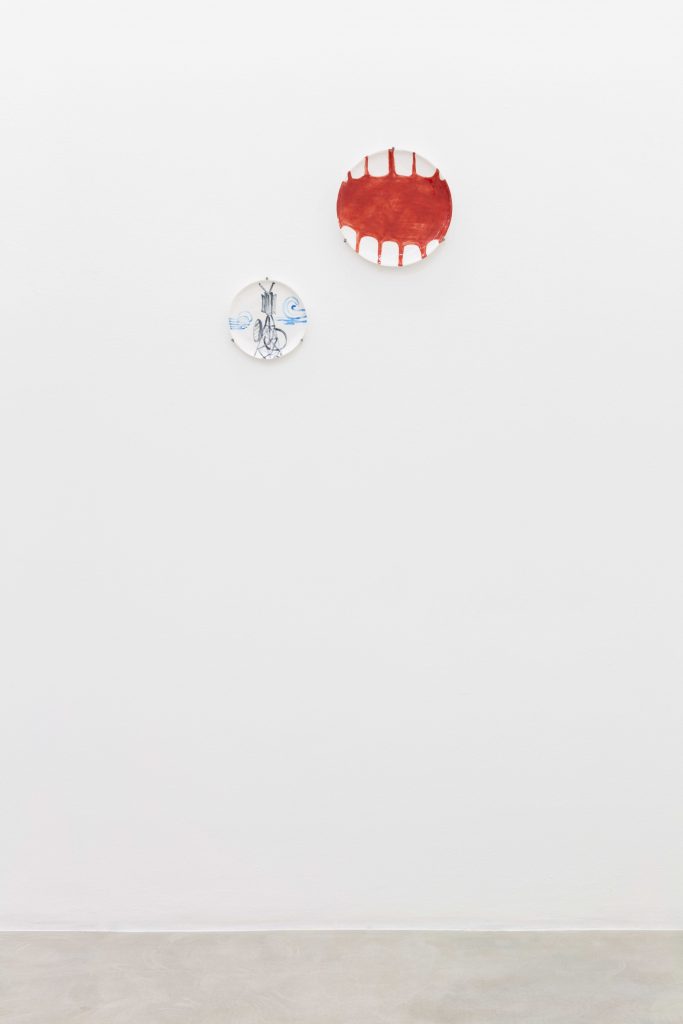

The critical scrutiny of dominant ideologies is also addressed in the other group of works presented in the exhibition. Two oversized grass blades are rising high in the spaces of the gallery. Monumental in scale – 3,50 meters tall one and 2,50 meters the other – they are realized in pressed steel and finished with a may-green powder coating. The industrial production process and the extreme enlargement confers a sense of abstraction on these two sculptural objects. With their towering height, the grass blades draw our attention to an omnipresent, but vastly overlooked botanical specimen. Grasses, sprouting abundantly on our planet for the past 55 million years, are arguably one of the most successful plant families, occurring in almost all ecosystems, with an extraordinary capacity to colonize, persist and transform environments. Due to its relevance for mammalian herbivory, grass assumed a fundamental role in the agricultural revolution during the Neolithic period. Forest clearance, one of the earliest man-made modifications of the natural environment, provided pastures for cattles, shortly followed by the introduction of fencing systems, leading to the appearance of property ownership, domestication of animals, collection of natural resources and the arising of ‘cultural landscapes’. In more recent centuries, cultivated grass became a constant presence on the pleasure grounds of the modern man: in the gardens of Renaissance villas and Baroque castles, in the 18th century Jardin à l’anglais and in the carefully trimmed lawns adorning suburban middle-class houses of the 20th century.

But the artist’s Blades of Grass are clearly not available for human use. By sheer size, they are placed out of our control, and being forced to look up at them we are obliged to revise our scale of values of what we normally consider to be great and important. This theme is also taken up in the two Endless Tree screen prints: each one 2,50 meter high, they depict tree stems whose growth is apparently perpetual and incessant, carelessly ignoring the limits of the picture frame. Unaffected by human categories, Hopf’s rebellious grasses and trees prompt us to investigate the place of plants in human systems of meaning, recently challenged by the discussion of vegetal intelligence and vegetal dignity, which culminated in the proclamation of a ‘plants’ rights carta’ by neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso. This radical ontological shift is also taken up by political theorist Jane Bennett’s thesis of “vital materiality”. Overcoming the dichotomy between human/non human animals opposed to inorganic matter, she theorizes that all entities have in common a lively and energetic play of forces: “Why advocate the vitality of matter? Because (…) the image of dead or thoroughly instrumentalized matter feeds human hubris and our earth-destroying fantasies of conquest and consumption. It does so by preventing us from detecting (seeing, hearing, telling, feeling) a fuller range of nonhuman powers circulating around and within human bodies.”*

Within this broader context, Hopf’s new works invite us to experiment a drastically different attitude, putting in doubt the human exceptionalism and the categories on which it rests. Her Blades of Grass and Endless Trees – not only placeholders for nature but also for ‘matter’ in a wider sense – are far from being inert, passive or humble objects. Their prodigious growth suggests the presence of an unruly, headstrong vitality – a vitality that certainly outclasses the helpless techno-addiction of the lethargic, clumsy Phone Users who have clearly lost the coordinates of a bygone, anthropocentric world. To conclude with Bennett, only by overcoming the figure of an intrinsically inanimate matter we will be able to advance “the emergence of more ecological and more sustainable modes of production and consumption”.**

Judith Hopf (b. 1969, Karlsruhe) lives and works in Berlin. Her work has been exhibited internationally at SMK – National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen (2018); KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2018); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2017); Museion, Bozen (2016); Neue Galerie, Kassel (2015); PRAXES, Berlin (2014); Kunsthalle Lingen, Lingen (2013); Studio Voltaire, London (2013); Fondazione Morra Greco, Naples (2013); Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Frankfurt (2013); Malmø Konsthall, Malmø (2012); Grazer Kunstverein, Graz (2012); Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe (2008); Portikus, Frankfurt (2007); Secession, Vienna (2006); Caso Institute for Art and Design, Utrecht (2006). She has participated in biennials and group exhibitions in international institutions, such as Lenbachhaus, Munich (2018); Mudam, Luxembourg (2017); La Biennale de Montreal (2016); 8th Liverpool Biennial, Liverpool (2014); Sculpture Center, New York (2014); Triennale for Video Art, Mechelen (2012); dOCUMENTA13, Kassel (2012); Kunsthalle Basel (2011); Kunsthall Oslo, Oslo (2010). Judith Hopf is professor at the Städelschule in Frankfurt.

* Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter. A Political Ecology of Things, Duke University Press, Durham e Londra 2010.

** Ibid.

kaufmann repetto è lieta di annunciare GROW, la quarta personale di Judith Hopf con la galleria. Nel suo nuovo progetto, l’artista presenta sculture e serigrafie, opere che rivalutano il nostro sistema di pensiero e che mettono in discussione il ruolo privilegiato dell’uomo nelle strutture gerarchiche dell’esistenza.

Con Phone Users 1, 2, 3 gli esseri umani compaiono sulla scena sotto forma di sculture a grandezza naturale realizzate in creta, una rappresentazione figurativa senza precedenti nella pratica dell’artista. Assemblati con frammenti modellati a mano, i contorni friabili dei corpi e dei lineamenti appaiono appena abbozzati. Catturate nell’isolamento silenzioso e immobile della loro materialità grezza ed effimera, le tre figure rappresentano delle persone che stringono un telefonino. I loro gesti evocano un’esperienza della nostra vita quotidiana che tutti conosciamo bene: sono infatti ritratte nel momento in cui ricevono, registrano o trasmettono dei segnali legati alla telecomunicazione. Ma questi “utenti telefonici” – che sollevino l’apparecchio in cerca di una migliore ricezione o che si pieghino goffamente sullo schermo per inviare un messaggio – sembrano in difficoltà, come se neppure loro sapessero cosa dovrebbero ricevere. Le loro espressioni trasmettono una sensazione di confusione: non riescono a credere che la loro connessione con il mondo non funzioni come avevano immaginato.

La preoccupazione per l’interrelazione fra esseri umani e tecnologia è un tema ricorrente nella produzione di Hopf: la ritroviamo per esempio in Laptop Men, una serie precedente di figure astratte composte da lamiere di metallo dalla forma geometrica, che sfoggiano volti da cartone animato. Anche in Phone Users è avvenuta una fusione completa fra corpo e dispositivo, eppure in questo caso si respira un’aria di resistenza, trasmessa dalla materialità grezza della creta, materiale vicino alla terra a livello tanto letterale quanto simbolico. La plasticità e la malleabilità della materia prima conservano il ricordo della modellazione manuale, poiché riproducono con estrema precisione ogni pressione esercitata dalle dita e dalle mani – un processo di scansione ante litteram che si contrappone alla dipendenza contemporanea dal digitale.

L’analisi critica delle ideologie dominanti emerge anche da un’altra serie di opere in mostra. Due enormi fili d’erba si innalzano negli spazi della galleria: dalle dimensioni monumentali (uno è alto 3,5 metri, l’altro 2,5), sono realizzati in acciaio pressato e rifiniti con una verniciatura a polvere verde. Il processo di produzione industriale e il sovradimensionamento conferiscono ai due oggetti scultorei una dimensione astratta. Grazie all’altezza imponente, i Blades of grass attirano la nostra attenzione su un esemplare botanico onnipresente ma spesso trascurato. L’erba, che cresce in abbondanza sul nostro pianeta da 55 milioni di anni, è senza dubbio tra le piante più diffuse, dato che si trova in quasi tutti gli ecosistemi e ha una straordinaria capacità di colonizzare e trasformare gli ambienti in modo duraturo. Grazie alla sua importanza per i mammiferi erbivori, nel corso del Neolitico l’erba assunse un ruolo fondamentale nella rivoluzione agricola. La deforestazione che creò i pascoli per il bestiame è stato uno dei primi interventi con cui l’uomo ha modificato l’ambiente naturale, seguito rapidamente dall’introduzione dei recinti, dalla comparsa della proprietà dei terreni, portando all’addomesticazione degli animali, alla raccolta delle risorse naturali e alla nascita dei “paesaggi culturali”. In tempi più recenti, l’erba coltivata è diventata una presenza costante nei luoghi di piacere dell’uomo moderno: la troviamo nei giardini delle ville rinascimentali e dei castelli barocchi, così come nel Jardin à l’anglais del Settecento e nei praticelli curati che decorano le case nei sobborghi della classe media nel Novecento.

Ma è chiaro che i Blades of grass dell’artista non sono disponibili per l’utilizzo umano. Le loro dimensioni li sottraggono al nostro controllo e noi, costretti a guardarli dal basso, non possiamo che rivedere la scala di valori di ciò che in genere consideriamo grande e importante. Una tematica affrontata anche nelle due serigrafie Endless Tree: alte 2,5 metri, mostrano i fusti di due alberi che sembrano crescere in modo perpetuo e incessante, ignorando con noncuranza i limiti imposti dalla cornice. Imperturbati dalle categorie umane, gli alberi e l’erba ribelli di Hopf ci spingono ad analizzare il ruolo occupato dalle piante nei sistemi di significato umani, sfidati di recente dal dibattito sull’intelligenza e sulla dignità dei vegetali, culminato nella proclamazione di una“carta dei diritti delle piante” firmata dal neurobiologo Stefano Mancuso. Questa svolta ontologica radicale è condivisa anche dalla tesi della “materialità vitale” messa a punto da Jane Bennett, teorica politica. Superando la dicotomia che contrappone gli animali umani/non umani alla materia inorganica, Bennett teorizza che ad accomunare tutte le entità sia un gioco di forze vivace ed energico: “Perché sostenere la vitalità della materia? Perché […] l’immagine della materia morta o profondamente strumentalizzata alimenta la tracotanza umana e le nostre fantasie di conquista e consumo che finiscono per distruggere la terra. E lo fa impedendoci di cogliere (vedere, udire, raccontare, sentire) una più ampia gamma di poteri non umani che circolano attorno e all’interno dei corpi umani”.*

In questo più ampio contesto, le nuove opere di Hopf ci invitano a sperimentare con un atteggiamento drasticamente diverso, che mette in dubbio il carattere eccezionale dell’essere umano e le categorie su cui esso si fonda. Blades of Grass ed Endless Trees – rappresentanti non soltanto della natura, ma pure della “materia” in senso più vasto – non sono affatto oggetti inerti, passivi o modesti. La loro crescita prodigiosa suggerisce la presenza di una vitalità insubordinata e risoluta, una vitalità che di certo surclassa l’indifesa dipendenza tecnologica degli indolenti e goffi “utenti telefonici”, che hanno chiaramente smarrito le coordinate di un mondo antropocentrico che ormai appartiene al passato. Per concludere con le parole di Bennett, solo superando la figura di unamateria intrinsecamente inanimata riusciremo a far avanzare “l’emergenza di modalità di produzione e consumo più ecologiche e sostenibili”.**

Judith Hopf (Karlsruhe, 1969) vive e lavora a Berlino. Le sue opere sono state esposte in tutto il mondo, in istituzioni come: SMK – National Gallery of Denmark, Copenaghen (2018); KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlino (2018); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2017); Museion, Bolzano (2016); Neue Galerie, Kassel (2015); PRAXES, Berlino (2014); Kunsthalle Lingen, Lingen (2013); Studio Voltaire, Londra (2013); Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli (2013); Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Francoforte (2013); Malmø Konsthall, Malmø (2012); Grazer Kunstverein, Graz (2012); Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe (2008); Portikus, Francoforte (2007); Secession, Vienna (2006); Caso Institute for Art and Design, Utrecht (2006). Ha partecipato a biennali e mostre collettive organizzate da istituzioni internazionali, tra cui: Lenbachhaus, Monaco (2018); Mudam, Lussemburgo (2017); La Biennale de Montréal (2016); 8th Liverpool Biennial, Liverpool (2014); Sculpture Center, New York (2014); Triennale for Video Art, Malines (2012); dOCUMENTA13, Kassel (2012); Kunsthalle Basel (2011); Kunsthall Oslo, Oslo (2010). Judith Hopf è professoressa al dipartimento di Belle Arti presso la Städelschule di Francoforte.

* Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter. A Political Ecology of Things, Duke University Press, Durham e Londra 2010.

* Ibidem.