- This event has passed.

lily van der stokker is one of the Netherlands’ most celebrated contemporary artists. In 1983 she moved to New York, opening a small artist-run gallery space in the East Village and has since lived alternately in both New York City and Amsterdam.

For over 30 years, van der Stokker’s drawings and monumental wall paintings have subverted artistic convention and aesthetic expectations, employing an Easter candy color palette to depict clouds, flowers, swirls, and other traditionally feminine or decorative motifs. Van der Stokker annotates these compositions with handwritten text—spelling out intimate thoughts, personal musings, notes-to-self and social niceties. Her visual language is nostalgic and comforting; her playful squiggly patterns are more likely at home in the margins of a student’s notebook as they mindlessly doodle or test out their first name with the surname of a crush than they are within the white walls of a gallery. In fact, van der Stokker’s practice is in some ways defined by this incongruity. She notes, “if I make an artwork about family problems, administrative tasks, or the common flu…I’m bringing in a whole spectrum of new subject matter that is normally absent in art.” By placing on a pedestal what has traditionally been viewed as feminine or domestic, and thus superfluous and inconsequential within the realm of “serious” visual art, van der Stokker reclaims what has long been disregarded and overlooked.

In a 1990 New York Times review of van der Stokker’s debut exhibition, critic Roberta Smith remarked, “the messages conveyed in this terminally cheerful manner usually have a double edge.” Van der Stokker’s work, which she has referred to as “feminist conceptual pop art,” is undeniably joyful and positive, however, it often simultaneously speaks to weighty themes—aging, health, and, more generally, the lived experience of being a woman within patriarchal structures. Hidden in plain sight, disguised by the veneer of her compositions’ cute and charming appearances, is reality. Occasionally mundane, sometimes cheery, and at other moments, cynical or intimate—“a baby, another baby…all my no baby friends live in N.Y.,” a past mural reads. One divulges, “whoopy doo…I am…really ugly…sorry,” in cartoonish thought bubbles. “My mother will loan me €80,000 to help me buy the house,” another reveals. Van der Stokker considers the texts to be the primary component of her work, and with each work she lays bare a vulnerable inner-world for all to see—if they’re willing to look beyond the candy-coated facade.

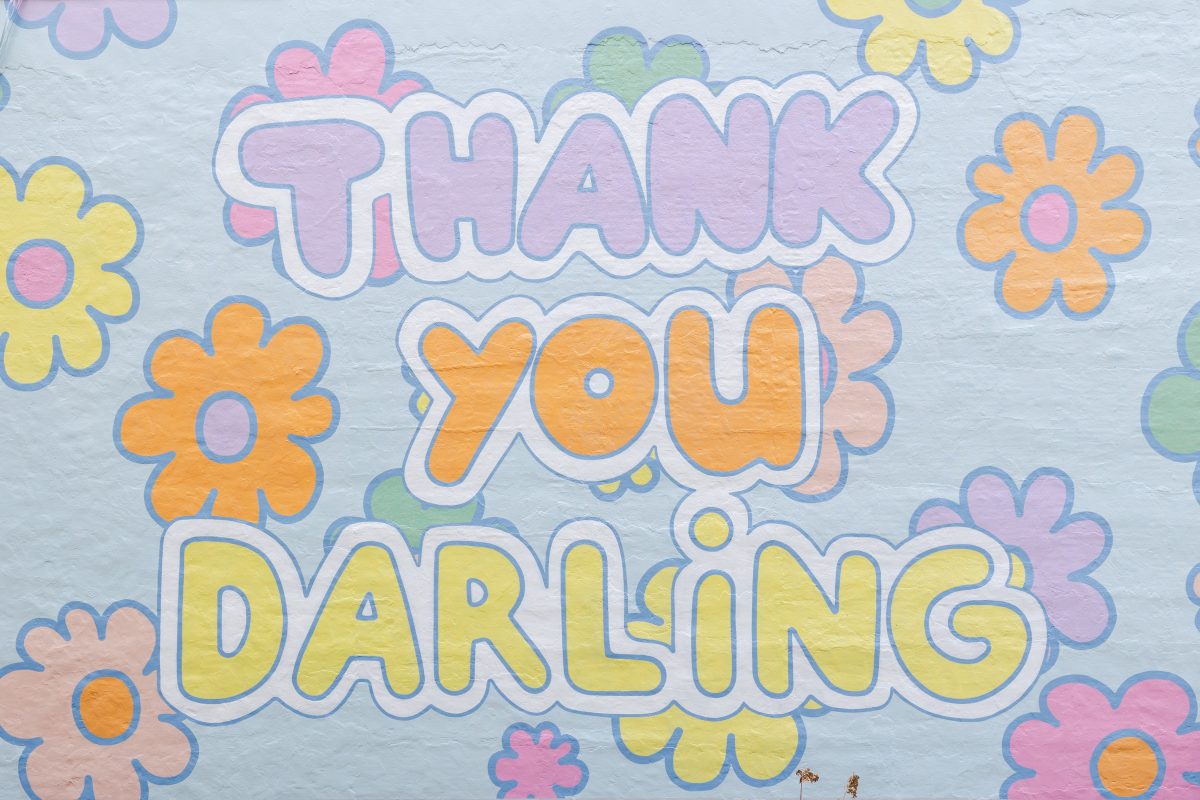

On the High Line, van der Stokker presents Thank You Darling, a monumental, site-specific mural. Thank You Darling is painted on the side of a building, turning the architecture and shape of the edifice into the frame for the artist’s pastel and fluorescent-hued work. The light blue background is dotted with multi-colored, simple flowers in a decorative all-over pattern that appear to float across the facade—some just coming into view from the edges of the frame. Superimposed over this, read the words “THANK YOU DARLiNG,” spelled out in a juvenile, arbitrary blend of lower and upper-case lettering. Van der Stokker’s puffy bubble-letters are a classic example of playful adolescent penmanship, seemingly lifted right out of a teenager’s diary. In this location on 22nd street, Thank You Darling actively engages with its audience, expressing gratitude to all those who pass, while reclaiming, at massive scale, intimate language that is often mocked or disparaged as being feminine and unserious.